While the U.S. has rightly focused on Ukraine and the nearby members of NATO, Russia and China have launched serious threats to Russia’s other former colonies in Central Asia. Washington has all but ignored these initiatives. If this does not change, the entire zone between the East China Sea and the Middle East could end up under the domination of these two authoritarian powers, which are hostile to America.

Besides its numerous threats to invade Kazakhstan, Moscow is actively courting the five Central Asian states. Since the start of the war in Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin has brought all five presidents twice to Moscow and personally visited the region several times. His goal is to preserve what he can of what he calls the “Russian realm” at a time when it is crumbling in Ukraine, and to counter Beijing’s hyper-active initiatives in the region.

Meanwhile, China’s Xi Jinping convened the five presidents in Beijing on May 21st, at which time he announced the creation of China’s own grand development plan for the region, which will be launched when he again meets all five presidents in Tashkent later this year.

Reporting on these developments, Central Asians never fail to note that, since their new nations gained independence in 1991, no U.S. president has ever visited the region and that there are no prospects for such a visit until at least after the American elections in the Fall of 2024.

That is a mistake. Like the Baltic states and Ukraine, all five Central Asian countries are struggling to preserve their independence. While they have no choice but to build good relations with their superpower neighbors, they have all actively sought American help in balancing the aspirations of China and Russia.

Washington, however, has never really brought Central Asia into focus. For more than two decades, U.S. strategy subordinated the entire region to its concerns in Afghanistan. Central Asians cooperated by opening their territories to the transport of NATO war materiel, but the U.S. and NATO did not reciprocate. These landlocked countries urgently pleaded for the West to open a transport route across Afghanistan to the southern seas, India and Southeast Asia. Without it, they argued, they would remain dependent on Russia and China for access to world markets. But Washington turned a deaf ear.

Back in 2015, then-Secretary of State John Kerry approved the creation of the “C5+1,” a consultative body involving all five Central Asian states and the U.S. However, this project – a copy of arrangements that Japan, Korea, and the EU had long since instituted – was proposed not by Washington but by Kazakhstan. While it now meets regularly, and current Secretary of State Antony Blinken attended the most recent meeting in Kazakhstan, the C5+1 is viewed in the region as just another talk shop. Disappointed, Central Asians wonder why the U.S. is so passive in advancing its own interests in their region.

In September, the United States has what might very well be its last chance to play the kind of balancing role that will prevent Central Asia from coming solely under the purview of China and Russia. The annual meeting of the United Nations will bring all five presidents to New York. If President Biden were to convene a meeting of the C5+1 during their visit, it would symbolize the end of three decades of neglect. Such a meeting, moreover, should avoid America’s usual “projectitis” and focus instead on security in all its dimensions. Only low-level representatives from the Department of Defense have attended previous meetings. The C5+1 should also take concrete measures to advance trans-Caspian trade and energy transport, lest this be dominated by China as well. To this end, it should consider adding Azerbaijan to its ranks. Finally, it should establish a permanent and well-staffed office, possibly in the region itself.

Few tasks in Washington are more challenging than to claim a day of the President’s time. However, if the National Security Council, State Department, and Pentagon link arms, it might just be possible.

As the White House weighs such a proposal, it must recognize the price it will pay for not embracing it. Whatever the outcome in Ukraine, Russia will eventually shift its attention to the rest of its Eurasian project. Central Asia and the Caucasus are the only place where Moscow can still advance this fantasy. Meanwhile, the fact that China is outmaneuvering Moscow in the region only serves to remind us of Beijing’s larger aspirations, which embrace all Central Asia as much as Taiwan. Thus, the region is crucial to the geopolitical ambitions of both Moscow and Beijing. The world will watch intently for America’s response.

Central Asians have no intention to roll back their ties with their large neighbors, but seek rather to balance them with ties with the West. However, recent polls in the region indicate that the majority of their publics have abandoned hope of enhanced ties with America and Europe and are struggling instead to figure out how to preserve their sovereignty in the face of China and Russia. America now has before it what may be the last, best chance to prevent the region from being dominated by autocratic outsiders. This, no less than the fate of Ukraine and the newly independent states of Europe, will shape the future.

The ball today lies in the hands of President Biden’s schedulers.

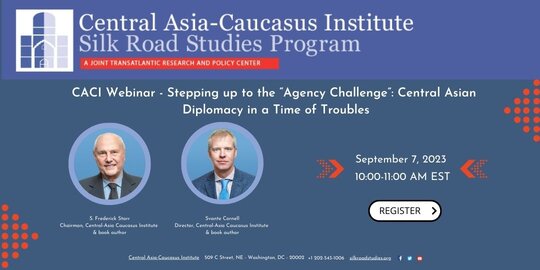

S. Frederick Starr is Chairman of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute at the American Foreign Policy Council.